On Thursday, the US passed a grim milestone: it surpassed China as the country with the largest number of confirmed coronavirus cases. The milestone was reached during what appears to be a growing public tug-of-war between senior Trump administration officials, who wish to see restrictions lifted as quickly as possible, and public health experts, who argue they're clearly still required for the time being. That tension may end up playing out in the implementation of a new plan being developed to guide states through their response to the pandemic.

One casualty in this fight: the work of epidemiologists. As these researchers continue to test the impact of different restrictions on the spread of infections, their models are necessarily producing different numbers. Those differences are now being dragged into the intensely political arguments about how best to respond to the pandemic.

Grim numbers

As of this writing, the world has seen slightly under 560,000 confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Of those, 86,000 (about 15 percent) are in the US. China, where the pandemic originated, is near 82,000 cases, followed by Italy with a bit over 80,000. All of the other countries with over 10,000 confirmed cases are European, with the exception of Iran.

China is indicating that the majority of its cases are now due to secondary re-introduction: the virus has largely stopped circulating within the populace, but travelers from countries with unchecked spread are now bringing it back with them.

China is in a position to track new infections because it imposed significant restrictions on its population and then ramped up testing so that new instances of transmission could be identified quickly. Despite having advanced warning of the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the US's failure to ramp up testing allowed the virus to establish itself in many areas of the country. As a result, many states have been compelled to place severe restrictions on their populace in the hope of limiting the rapidly spreading infections.

The public health goal of these restrictions is partly to reproduce what China claims to have achieved: a combination of limited infections and rapid testing that allow the US to identify and isolate recently infected individuals and trace anyone they interacted with. (It's also to limit the number of severe cases so they can remain within the capacity of our health care system.)

While this goal hasn't been clearly communicated by this administration, there are indications that's starting to change. On Thursday, Trump sent a letter to US governors that contained a rough outline of a plan for containing the virus. The plan will involve extensive testing to identify the state of the virus on a per-county level. Counties will be placed in different risk categories according to the results of that testing, and the governors will be given a set of restrictions that should be put in place to help bring the risk down.

This approach is necessary in the US because the structure of government places authority for health issues in the hands of states. There is simply no mechanism by which the President can directly compel local authorities to implement these sorts of public health restrictions.

Unfortunately, that structure could threaten to undermine this program. Trump has generally tended to downplay the risk posed by SARS-CoV-2 and push the prospects of a return to normal activities, despite opposition by public health experts both within and outside the administration. While that tension is likely to play out in the crafting of the guidelines for this new policy, a number of Republican governors have decided to take an approach in keeping with Trump's wishes and declined to implement restrictions.

Everything is political

While policy decisions like this are the natural domain of partisan politics, partisanship has now intruded on a rather unexpected area: epidemiology. A major factor in the decision to place heavy restrictions on public interactions was the production of epidemiology models that explored how the virus might spread and what that could mean for our public health systems. By necessity, these models require a number of assumptions about a disease we have only partial information on. As we mentioned in our initial coverage, however, the key model attempted to base these assumptions on empirical data as much as possible.

Naturally, however, that has not stopped epidemiologists—including some of the ones involved in the earlier study—from trying out alternate assumptions. These have included assumptions that really have little basis in reality, such as assuming that a very large number of those infected are essentially symptom-free. But it has also involved trying to model what will happen if countries put specific restrictions in place at different points in the growth curve of their national virus outbreak—something that is happening in the real world.

Naturally, these different epidemiological models produce different results—that's the whole point of running multiple models. None of them are necessarily wrong or right, but the hope is that some of them are useful. The problem comes when those different results get publicized without this context and are weaponized through partisan politics.

Take, for example, the idea that there might be a large number of symptom-free infections. In the model that resulted, this allowed herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 to be established quickly, and without the strain on the medical system caused by large numbers of people with severe symptoms. Which, of course, sounds great, other than the lack of data that suggests this is what's happening in the real world. Unfortunately, the Financial Times ran a story on that model without mentioning that significant caveat or asking for outside experts to comment on the issue. That forced the publication backtrack quickly as criticism poured in.

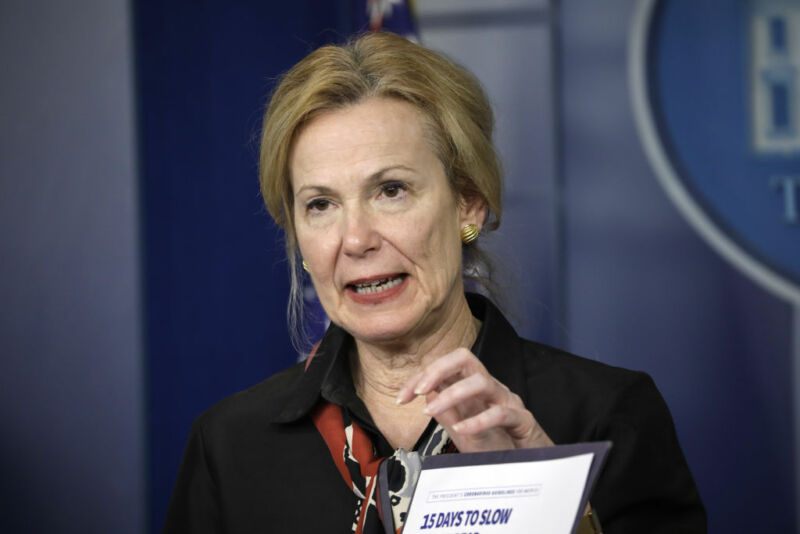

Unfortunately, this situation has been explained poorly by Trump Administration officials. Deborah Birx, who is the coordinator of the Coronavirus Task Force, discussed yesterday how many of the models don't match the empirical data we're getting from various countries. It turns out there's a good reason for that: Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch says that his team was specifically asked to model dozens of different scenarios by the CDC in order to give a broader picture of what the US might see under different circumstances.

Naturally, this statement was picked up by the press as Birx cautioning against "inaccurate models" (though her statement was more a caution about not trusting every single model). Any nuance in Birx's statement was lost by the time criticisms reached the partisan editorialists at Fox News and the Wall Street Journal.

All of which led epidemiologist Carl Bergstrom to publish a long lament on Twitter. We'll quote part of it below:

As infectious disease epidemiologists, biomedical researchers, and health professionals more broadly, we're fighting a battle against the biggest crisis in decades. But we are also fighting on a second front that we did not anticipate, fighting a battle against misinformation and disinformation in a hyper-partisan environment where our predictions and recommendations about the pandemic response are deeply politicized. Every twist and turn that the pandemic takes is seized upon by one side or other to claim that some fraction of us are incompetent if not outright mendacious.

Researchers are pilloried for updating their beliefs based on new information. In this environment, when unexpected facts come to light—a higher than anticipated [infectivity], for example—they are used to discredit scientists who made correct inferences given the data that they had available at the time.

To understand this pandemic, it's part of a scientist's job to produce numbers and projections, even though we know in advance that some of those will be wrong. Being wrong doesn't mean the models are useless or that the scientists were wrong. And it doesn't mean that the scientists are confused or know little about what they're modeling. These numbers are produced because they show the contrast between our actions and doing nothing—or what might happen if the virus turns out to behave differently than it appears to be.

This is a case where misinterpreting why those numbers exist for partisan purposes may directly cost lives within the next few months.

"plan" - Google News

March 28, 2020 at 02:43AM

https://ift.tt/2wypAGT

US finally has plans for the pandemic it now leads in infections - Ars Technica

"plan" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2un5VYV

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "US finally has plans for the pandemic it now leads in infections - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment