So much is written about marital conflicts in academic and popular literature as well as scads of social media. My complaint about most of this literature is that it confounds what is a marital conflict with the usual and typical disagreements or differences between spouses. These are qualitatively different kinds of interactions.

This post is about identifying the difference between conflicts and disagreements and how to address both types of marital interactions.

Disagreements vs. Conflicts

Disagreements or differences between partners are about what you and your partner want in the relationship. When you disagree with your partner, it is about something—e.g., an activity, an event, a chore. You can differ on all kinds of things—what movie to see, how to discipline a child, when to have sex, where to get the car serviced, etc.

The defining thing about differences and disagreements is that you are talking to each other—you are negotiating a resolution of the difference between you. You can look for a win-win outcome. One of you can make an accommodation to the other, or you can agree to disagree and move on. The most important thing is that during and after the disagreement you are talking to each other.

Conflict is different. In a conflict, you are not talking to each other; you are yelling, calling each other names, swearing at each other, talking over each other, etc. In a conflict, the thing that elicited the conflict is not resolved because you do not negotiate, you react. You react emotionally, typically with anger, fear, and hurt, setting the stage for conflict to occur.

Elements of a Marital Conflict

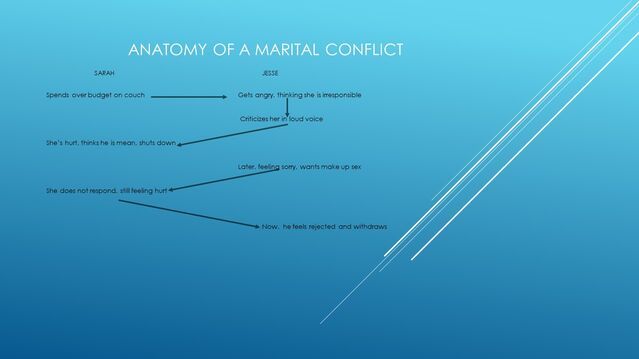

One definition of anatomy is a study of the internal workings of something. I want to take you through the internal workings of a marital conflict so that you will be able to: recognize when it is occurring, resolve the conflict, address the disagreement, and learn something new about yourself.

Recognizing a Conflict

The schematic below depicts a conflict occurring between Jesse and Sarah over how she spent money on a new couch for their apartment. Sarah spent more than she and Jesse had agreed upon. When she told Jesse this, he immediately got angry at her seeing her as acting “irresponsibly." He verbally criticized her, calling her “irresponsible” in a raised voice. Jesse will “make a case” about her irresponsibility by highlighting past times she spent over the budget, citing even minor “transgressions." He is justifying his anger and his reaction—without a discussion with her about what she did.

Sarah, in turn, seeing Jesse’s characterization of her as “irresponsible” as not justified, feels hurt and angry. She makes no attempt to explain why she spent more than they had agreed upon.

Jesse and Sarah now have a conflict that goes unresolved. They went their separate ways the rest of the day. Later that evening, Jesse, feeling less angry and a little sorry for what he had said, approaches Sarah amorously. She, still reeling from his accusations and feeling misunderstood, is not inclined to respond to his amorous approach. She still sees him as unkind and unfair. Alas, Jesse now feels rejected and withdraws.

Taking Things Personally

When you are angry, hurt, anxious, fearful in these situations, you will characterize not describe what your partner did. Jesse characterizes Sarah as irresponsible rather than describing her spending over the budget as a concern for them to discuss. Sarah characterizes Jesse as domineering rather than expressing her concern that he thinks she is irresponsible. You then justify your emotional reacting by the characterization you created—Jesse’s anger is justified because Sarah is irresponsible. Sarah feels hurt and shuts down because Jesse is domineering.

Others rarely, if ever, experience their own actions in the same way that you characterize them. Sarah will never see herself as “irresponsible”; she may agree that she made an error, or that she did not keep to their agreement, or that she could have crosschecked with Jesse—but she will not characterize these actions as “irresponsible.”

When you characterize your partner instead of describing what the issue for you is, you are reacting personally. When this happens, you will be at risk to trigger a conflict rather than address a disagreement or difference between you and your partner.

What might be the personal reaction that is triggered by Sarah both spending over the agreed-upon budget and not consulting Jesse about her decision to do this? What might the threat to him be? How about not being “important” enough for her to check with him? Fear that he is losing his influence with her? Does he fear he might not be enough of an earner to satisfy her?

Learning About Yourself Through Self-Reflection

Conflict is not resolved through negotiation because it is no longer about the spending over the budget—the something of disagreements. It is now about who is wrong, who has acted badly, who should apologize, etc. It is now about the relationship—about the way you are interacting with one another.

Conflict is addressed through self-reflection, which means you are willing to take a hard look at your own personal motives when you react rather than interact with your partner, i.e. when you are “taking things personally."

If you would like to learn more about how to be self-reflective when you are “taking things personally,” take a look at my post, “How to Deal with Personal Insecurities in Your Marriage,” which has an inventory you can use to help you sort out just how “taking things personally” works. It is a useful tool. It will seem awkward to use at first but keep at it. It gets easier. You might even try working an inventory with your spouse, particularly if they reacted personally to your characterization of them.

Moving From Conflict to Disagreement

Once you have taken a step back from your emotional reaction and negative (it’s always negative) characterization of your partner, and if possible, taking your personal inventory, you can review the situation, addressing whatever disagreement or difference still exists.

Here is how Jesse turned the conflict into a disagreement.

- Once Jesse stepped away from his anger and negative characterization of Sarah, he wanted to talk to Sarah about why she spent more on the couch than they had budgeted.

- He arranged a time for them to talk. His first task was to apologize for his angry outburst. He noted that he was concerned both about the money that was spent, and that Sarah had not consulted with him about the spending over the agreed-upon budget.

- Sarah, having also addressed her own emotional reaction, made the case for the couch she bought. The couch was a high-quality piece of furniture with a significantly reduced price although still more than they had decided to spend. She had planned to use her own discretionary money to cover the extra cost of the couch.

- Jesse agreed that the purchase was a legitimate one—he also liked what she had selected. However, he was concerned that she had not contacted him about her decision.

- Sarah agreed that she should have consulted him prior to the purchase.

- From this discussion, they agreed to set a limit on what they could each spend over budget in a given situation without talking with each other.

Going through the steps: recognizing a conflict, being self-reflective about their personal reactions, and discussing the resulting disagreement or difference allowed Jesse and Sarah to reach a win-win solution to the issue at hand.

"conflict" - Google News

June 17, 2021 at 07:11AM

https://ift.tt/35viwZb

Anatomy of a Marital Conflict - Psychology Today

"conflict" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bZ36xX

https://ift.tt/3aYn0I8

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Anatomy of a Marital Conflict - Psychology Today"

Post a Comment