Illustration: Soohee Cho/The Intercept

“I’m surprised that so many Democrats are running on getting rid of it,” Biden said in a video publicizing his health care platform. “The Affordable Care Act was a historic achievement for President Obama, and if I’m elected president, I’m going to do everything in my power to protect it and build on it.”

His plan to “build” on the ACA is mainly to further subsidize it while leaving the basic structure unchanged: to increase subsidies and put a cap on premiums, to extend subsidy eligibility, and to add a public option. That, argues Biden, is the soundest and most fiscally prudent approach. Yet when it comes to actually making the system operate well, there’s a record that can be reviewed to gauge how reasonable a promise Biden is making. Across the country, Democrat-controlled states have had over a decade to work on improving the law, relying on existing authorities or ones they could acquire legislatively or through administrative waiver.

The record is clear. Even without the partisan obstacles of a nihilistic Republican opposition, Democrats have failed to build on the Affordable Care Act — not from a lack of good intentions, but because of the fatal complexity of the law itself. That same complexity has kept the media from reporting on Democratic failures to build on its own law, which has created the space for Biden to be able to pretend that he’ll be able to do so. But ultimately, it’s as if the party still hasn’t figured out how to get the lights to work in the house, but are confident the answer is an expensive addition.

It has been 10 years since the Affordable Care Act was signed into law and six years since the exchanges started, but many Democratic states still aren’t effectively managing their marketplaces. This has not been due to malice, budget constraints, or industry opposition. It is mainly because the system creates such a complex series of counterintuitive provisions that most state policymakers don’t understand the law or how to maximize every lever at their disposal.

Collectively, these regulatory decisions made in blue states have cost low-income individuals billions, and needlessly caused tens of thousands to go uninsured. The fact that Democratic states currently have the power to make the ACA noticeably better, but simply haven’t because they don’t understand their own law, shouldn’t fill one with confidence about the party’s ability to build on it by just adding more money.

Take the way that the government’s subsidies for lower-income people are calculated, a major source of the law’s problems. An individual’s subsidies are determined by calculating how much is required to make the second-cheapest silver plan cost them a set percent of their income. That’s a level of design complexity that should have been rooted out in the beginning; instead, everything else is based on it. This means, perversely, that the lower official premiums are in one’s area for that second-cheapest silver plan, the more low-income people actually have to pay for health care.

This issue is compounded by the fact that the Obama administration also decided to give insurers lots of freedom in how they design their insurance plans’ weird blend of copays, coinsurance rules, and deductibles. All silver plans were originally supposed to cover the cost of 70 percent of average covered benefits, also known as actuarial value or AV. The Obama administration brought that number to 68, and the Trump administration has since lowered it to 66 percent.

While states have the ability to require insurance companies to offer silver plans that cover nearly 72 percent, almost none do. New York regulators require silver plans to cover at least 70 percent. California regulators have also required insurers to only sell one standardized silver plan that covers 71.8 percent since 2014, and finally this year, Connecticut regulators followed suit. In many Democratic states, the silver plan on which subsidies are calculated are ones that are as close to 66 percent AV as possible. Prohibiting these low value silver plans would cost the state nothing and would help both consumers and insurance companies, but almost none do it.

Insurance companies, quite naturally, are gaming the system by offering multiple, nearly identical plans.

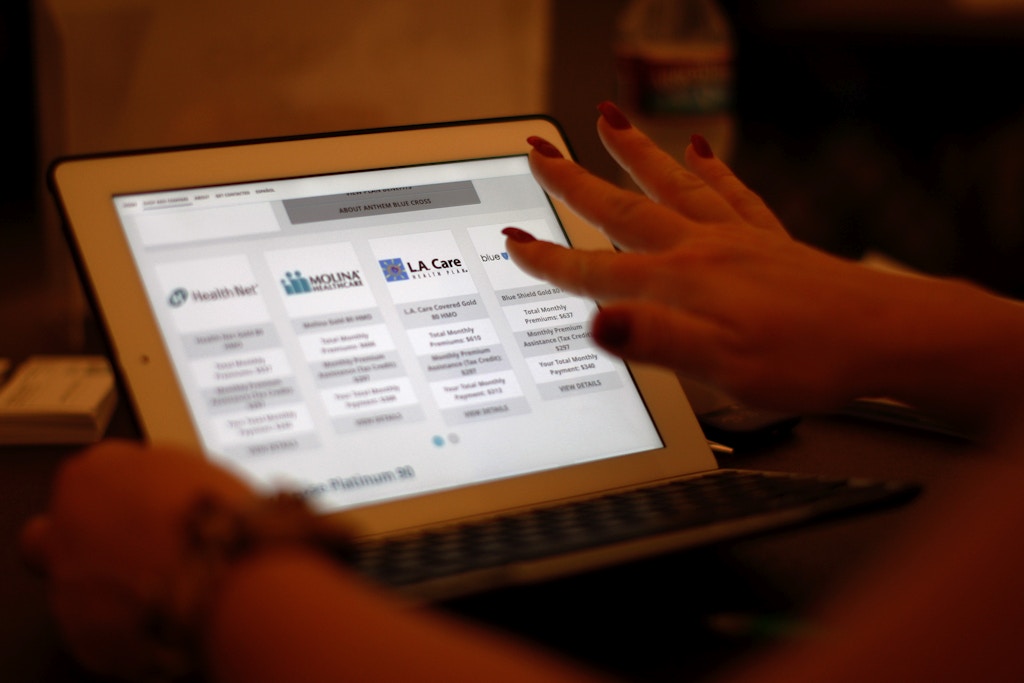

If the insurance market includes buyers and sellers, complexity introduced into that market gives a clear advantage in the transaction to the seller — who creates the products, writes the language describing it, and sets the prices. They have an army of functionaries dedicated to the task; the buyer has at most a few hours they can afford to spend looking over the impenetrable paperwork. Insurance companies, quite naturally, are gaming the system by offering multiple, nearly identical plans. This ensures that subsidies go to one of their cheap, narrow-network plans rather than a competitor’s, making it difficult for low-income people to afford insurance from any other company. California and now Connecticut prevent this by only allowing insurance to sell one standard silver plan, but most states, including blue states, allow it. This not only makes insurance more expensive, it also significantly reduces an individual’s choice of providers and makes shopping for insurance much more confusing.

There are some efforts in other Democratic-controlled states to stop this practice. For example, in Virginia this year, state Sen. Creigh Deeds, a Democrat, introduced a bill to prevent insurers from offering two narrow-network plans, but Deeds told The Intercept its passage is in no way guaranteed. “I have too many bills,” Deeds told The Intercept. “I don’t have time to work the bill the way I want to.” With so many issues to address this session, complex technical fixes to deal with the poor design of the ACA’s subsidy calculation — to ultimately help a small share of low-income residents — easily get lost in the scrum.

This mishmash of incentives ends up hurting the working class. Last year, Colorado adopted a much-hailed reinsurance program — intended to reduce what insurances companies paid out, and therefore what they charge insurees. While it did reduce premiums for the segment of relatively well-off people paying full price for insurance on the exchange, it actually cut subsidies for low-income individuals, driving up their individual cost. Similarly, the public insurance plan run by Los Angeles made insurance cheaper for higher-income people in some years, but in 2018 made coverage marginally more expensive for some who qualified for subsidies. Recent efforts by Democrats to improve the insurance market in Maine by merging the individual market with the small business market could easily backfire by just increasing costs for businesses with most of the savings going to the federal government instead of individuals.

A health care reform specialist helps people select insurance plans at the free Affordable Care Act Enrollment Fair at Pasadena City College on Nov. 19, 2013, in Pasadena, California.

Photo: David McNew/Getty Images

California stands out as the blue state where regulators and legislators have the best grasp of the ACA exchanges and how to build on them. From the beginning, California set up an active purchaser exchange and standardized its plans. Instead of chasing lower official premiums, it focused on how the system impacted most exchange users. This year, California even started providing over $300 million in state subsidies for those who make too much in income to qualify for federal help. However, even California has dropped the ball in important ways.

One of the best ways to get people to sign up for insurance is to make it free. For whatever reason, even premiums as low as $1 a month deter thousands. However, free plans don’t exist in California. Some blue states like California and Oregon require insurance to cover abortion, but federal law prohibits subsidies from paying for this coverage. This means the lowest-cost plan after subsidies must cost individuals at least a dollar a month, despite abortion coverage costing much less than a dollar a month. California could use state funds to directly pay for abortion coverage for exchange users, a move that would only cost a few million dollars. To put that in perspective, California spends $121 million a year just on outreach to encourage people to sign up for insurance. Spending a few million dollars to make some plans free would likely increase enrollment by tens of thousands — which would bring hundreds of millions in additional federal subsidies into the state, money California is leaving on the table.

The ACA allows insurance companies to charge older people three times as much as young people for insurance. Although states can require insurers to charge everyone the same price, only New York and Vermont do as a result of rules older than the ACA. The idea was to make insurance premiums cheaper for young people — who are less likely to need insurance — to get them to sign up. Once again, the subsidy design of the ACA creates a huge problem.

According to the ACA, the higher official premiums are for an individual, the larger their subsidies are. So if premiums are lower for young people, then their subsidies also go down. For example, in Los Angeles, a 31-year-old making $40,000 a year would need to pay $220 a month for the cheapest bronze plan after subsidies, but a 60-year-old need only pay $110 a month.

The age rule makes the whole system dramatically more complex. Insurance on the exchange is offered at four levels — bronze, silver, gold, and platinum — with the intent to make shopping easier. Bronze plans have the highest cost-sharing but lowest premiums while Platinum plans have the lowest cost-sharing but highest premiums. The problem is letting insurers charge people more based on their age makes designing plans and advising consumers dramatically harder. While premiums can vary by age, the deductibles and out-of-pocket limits for these plans must be the same for all ages. Take the example above. If the 31-year-old has medical issues that require significant care, the best overall value for them is to buy a so-called platinum plan that offers the lowest deductible. However, this is not the case for everyone. A 60-year-old with similar medical issues should actually buy a bronze plan because the higher premiums for a platinum will actually cost them more than they could save from having a lower deductible.The weird interaction of the many regulatory elements of the ACA means as you get older, you should often counterintuitively switch to buying “worse” coverage. This makes it impossible to design simple plans and universally applicable buyer guides, which are the linchpin of systems found in places like the Netherlands and Switzerland.

The big fix to the ACA that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is pushing is HR 5155. While it increases the size of the subsidies and removes the income cliff to qualify for subsidies, it does nothing to address the problems with how the subsidies are calculated or how insurers game the system. The same is true of Biden’s health care plan, which increases the current subsidies but says nothing about changing the rules to end insurers gaming the system, the generational inequality the rules currently cause, or the massive incentive it would give states to game the rules.

When the ACA passed, Sen. Tom Harkin, a Democrat from Iowa, was optimistic. “I like to think of this bill as like a starter home,” he said. “And this starter home has plenty of room for additions and improvements.” Yet in the past decade, this old house has proven surprisingly difficult to fix up. National Democrats who claim they want to build on the exchanges aren’t even talking about fixing its more obvious design issues, just throwing more money at it — all the while arguing that their solution is cheaper than a more holistic approach. Even with ample time, not a single blue state has successfully made even all of the most obvious improvements, needlessly depriving low-income people billions in federal help.

"plan" - Google News

March 06, 2020 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/2Irn07E

Why Biden's Plan to Expand the ACA Won't Work - The Intercept

"plan" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2un5VYV

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why Biden's Plan to Expand the ACA Won't Work - The Intercept"

Post a Comment