Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan may be poised to end a decade-long dispute over waters from the River Nile, agreeing on June 27 to conclude trilateral negotiations and reach final agreement about the first filling and annual operation of the massive 6.4-GW Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).

According to the Ethiopian Office of the Prime Minister, Ethiopia is scheduled to begin filling the GERD reservoir on the Blue Nile—a significant Nile tributary—within the next two weeks, “during which the remaining construction work will continue.” The office added: “It is in this period that the three countries have agreed to reach a final agreement of [a] few pending matters.”

Press Release on The Extraordinary Meeting of the Bureau of the African Union Assembly on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam#PMOEthiopia pic.twitter.com/a7168n6iL7

— Office of the Prime Minister – Ethiopia (@PMEthiopia) June 27, 2020

But according to a series of public statements from the Egyptian government over the past week, Egypt is pushing for a legally binding agreement under international law before filling can begin, and it has sought more international involvement in a resolution of the dispute. Still, Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok appears optimistic. He summarized the outcome of the summit last week simply: “It has been agreed upon that the dam filling will be delayed until an agreement is reached.”

A Gigantic Dispute

While the next two weeks will be pivotal to the three countries and for GERD’s progress, the agreement announced on Friday marks an important reprieve in escalating tensions between Ethiopia and Egypt after U.S.-mediated talks collapsed in February. Still, reaching a concrete resolution won’t be easy owing in large part to the demands of each country, as well as the ever-more complex negotiating landscape in which the resolution is being sought.

The agreement to invigorate talks last week was brokered by the African Union (AU) in an executive council virtual session that was chaired by South African president Cyril Ramaphosa and attended by notable African leaders, including the presidents of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, and Kenya.

It’s also especially notable that during that “Extraordinary Bureau of Assembly of Heads of State and Government” session on June 26, the AU pointedly requested the UN Security Council to “take note of the fact that the AU is seized of this matter.” The AU noted Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan are founding members of the pan-African body, and it underscored that the GERD project holds remarkable potential for the entire continent. AU Commission Chair Moussa Faki Mahamat also stressed that more than 90% of the issues in the “Tripartite Negotiations” between the three countries “have already been resolved.”

However, all three countries had representatives at a UN Security Council meeting on June 29 held to discuss the contentious dispute. In opening remarks on the matter, members from Indonesia, Belgium, and France applauded the AU’s leadership role in the matter. The Council’s involvement “should not be seen as precedent, but should be part of our collective efforts to resume negotiations, and to come up with amicable, acceptable, and implementable solution,” as the member from Indonesia noted.“In line with our long-standing position in advancing regional organization, we believe that resolving this issue in its original context is one of the best options.”

In a strongly worded speech delivered at that meeting, however, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry said the Security Council’s involvement is “necessary,” because the “eventuality” of any unilateral action by Ethiopia to begin filling the dam without a legally binding agreement under international law “represents a serious threat to international peace and security.” The dispute could “provoke crises and conflict that [could] further destabilize an already troubled region,” he warned.

But Egypt, which elected to bring the matter to the Security Council “to forestall further escalation and to ensure unilateral actions do not undermine efforts to reach an agreement on the GERD,” also introduced a draft resolution that Shoukry said was in line with the AU summit. “It encourages the three states to reach an agreement within two weeks, and not to take any unilateral measures in relation to the GERD, and emphasizes the important role of the U.N. Secretary General in this regard,” he said.

Why Is GERD So Contentious?

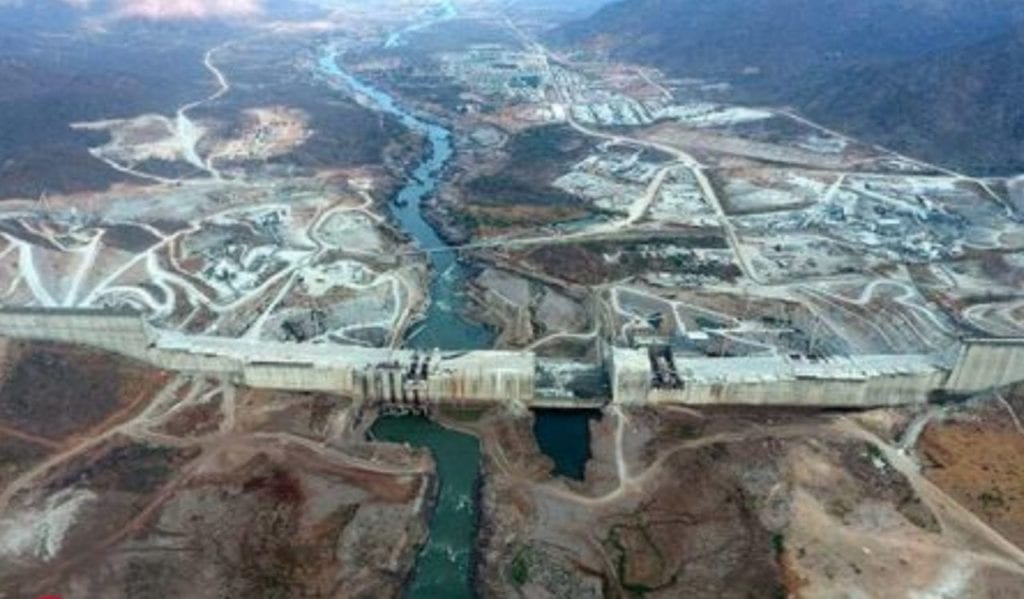

The developments are the latest in a long string of diplomatic haranguing about the mammoth $4.6 billion hydropower project. Since Ethiopia launched GERD in 2011, the project has garnered significant international scrutiny about its potential political, hydrological, environmental, and economic consequences, especially on Egypt and Sudan. These countries, which lie downstream from the dam’s location on the Blue Nile in the Eastern Nile basin, heavily depend on the Nile for freshwater supplies.

Egypt’s Shoukry put it starkly on Monday: “We in Egypt populate the most arid of the Nile Basin riparian states and one of the most water-impoverished nations on earth. This harsh reality compels us to inhabit no more than 7% of our territory along a slender strip of green and a fertile delta teeming with millions of souls, whose annual share of water is no more than 560 cubic meters, which places Egypt well below the international threshold of water scarcity,” he said. “Survival is not a question of choice, but an imperative of nature.”

But GERD is a landmark project for Ethiopia with extraordinary national significance—and Ethiopia frequently describes it as a pillar of its future economic and energy security. If built, it could more than double Ethiopia’s power capacity and render it into a formidable energy exporter in the energy-hungry East African region.

Located about 500 kilometers northwest of Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa, in the region of Benishangul-Gumuz-Gumaz, along the Blue Nile, the project is being built by Webuild Group, a subsidiary of Italian construction giant Salini Costruttori S.p.A. for state-owned Ethiopian Electric Power

Webuild says GERD is reportedly more than 70% complete. When completed, the hydroelectric project will be 1,800 meters (m) long, 155 m high, and have a total volume of 10.4 million cubic feet. The project involves construction of a main dam in roller compared concrete (RCC), with two power plants installed at the foot of the dam. It uses 16 Frances turbines each offering 375 MW. The project also involves a 15,000 m3/s capacity concrete spillway and a rockfall saddle dam.

A key point of contention is that the project will flood 1,700 square kilometers of forest in northwestern Ethiopia, creating a dam reservoir that could become nearly as large as Lake Tana, Ethiopia’s largest lake. Egypt contends that the structure is being built without “sufficient scientific data.

On Monday, Shoukry said: “If, God forbid, the GERD experiences structural failures or faults, it would place the Sudanese people under unimaginable peril and would expose Egypt to unthinkable hazards. Indeed, our concerns in this regard are not unwarranted. In 2010, the headrace tunnel of the Gibe II dam constructed across the Omo River collapsed within days of the completion of its construction.”

A Project of National Prosperity for Ethiopia

Despite various delays, Ethiopia asserts it has spared no effort in ensuring GERD will be successful. In a letter submitted to the UN Security Council in May, the country noted that Ethiopia is the source of 86% of Nile waters, but that for close to a century, “Egypt, through colonial-based treaties to which Ethiopia is not a party, saw to it that it received the lion’s share of Nile waters and introduced the self-claimed notion of ‘historic rights and current use’, leaving nothing to the remaining nine riparian countries.”

A landlocked country, Ethiopia claims it does not have a significant amount of groundwater resources or acquifers, or access to seawater for desalination, and owing to “climate change, drought, and erratic rains,” famine is a “constant threat” to around 8 million. Another 65 million, meanwhile, had no access to power. The country’s total power capacity is today only 4.5 GW, mostly derived from biomass, and “rising energy demand is exacerbating its energy insecurity,” the country noted. Ethiopia developed GERD as a national project funded “solely through the direct contributions of all Ethiopians because Egypt persistently blocked international financial institutions from supporting the construction of the dam.”

It’s also notable that Ethiopia deems GERD a vital project “of enormous potential for cooperation, regional economic integration and mutual benefits for countries in the region, including Egypt itself.” But though Ethiopia claims it has “demonstrated its commitment to foster cooperation and attain a win-win outcome,” it claims Egypt has been “dragging, stonewalling, and delaying the process as far and as long as possible.” It adds: “Although Ethiopia could fill the dam in two years, factoring in downstream concerns, we agreed to fill the GERD in stages that could take four to seven years. This filling schedule was accepted by Egypt.”

Tensions Cresting, Negotiations Continue

Shoukry noted on Monday that Egypt’s address to the UN Security Council and its participation in the AU summit stem from “successive stages of negotiations on GERD,” including “countless trilateral meetings” between the ministers of water affairs and their technical teams, ministers of foreign affairs to provide political support. The countries even established an “independent committee of hydrologists” to provide impartial scientific analysis of the scenarios of the filling and operation of the GERD. “Unfortunately, however, all of these efforts came to naught,” he said.

In March 2015, the countries struck an Agreement on Declaration of Principles for the GERD project, but while the treaty remains legally binding, Egypt claims an independent effort to conduct studies on the effects and impacts of the dam were impeded and never completed.

Tensions began to crest more aggressively starting this February, after Ethiopia shunned a U.S-brokered agreement with technical input from the World Bank. Blaming delays on Egyptian “stonewalling,” Ethiopia then publicly pronounced it would begin filling the reservoir during the rainy season this July without agreement from Egypt and Sudan. As the rainy season drew closer and Ethiopia prepared to move forward, trilateral negotiations were finally resumed by video conference between May 19 and June 17.

But on June 19, Egypt urged the UN Security Council in a letter “to intervene to emphasize the importance that three countries … continue negotiations in good faith.” In that letter, notably, Egypt pushed back strongly on a number of Ethiopia’s claims, including that Ethiopia lacked water resources. Egypt claimed Ethiopia “is a water rich country that mismanages its water resources,” while Egypt is a “water-scarce country that is entirely dependent on a single source of water that it uses with very high systemic efficiency.”

Egypt also contended Ethiopia’s claims that Egypt sought to impose a “historic right and current use” on Nile waters. Egypt asserted plainly that it is “entirely supportive of the right” of Ethiopia, and other riparian countries to Nile waters. It stressed, however, that GERD must be governed by principles applicable to international law, “which require preventing the causing of significant harm to existing water uses.”

Sudan, meanwhile, sent its own letter to the Security Council on June 25, warning that unilateral action would “compromise the safety of Sudan’s Roseires Dam and thus subject millions of people living downstream to great risk.”

Though Sudan decries unilateral action on GERD, it has also functioned as a notable intermediary to help resolve the dispute. Last week, the country reported that while the parties made significant progress on the main technical issues during conferences earlier this month—including as they pertain to the first filling, annual operation, mitigation measures, dam safety, data exchanges, and environmental and social issues—“a widening gap emerged” on issues of the “binding nature of the legal agreement, including amendments and termination.”

Also still to be resolved—though Egypt claims these are external to negotiations on GERD—are Ethiopia’s demands that it become part of a 1959 water sharing treaty between Egypt and Sudan within 10 years, Sudan said.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).

"conflict" - Google News

July 02, 2020 at 10:07PM

https://ift.tt/2YPZQ3Y

Egypt Warns Ethiopian Mega-Dam May Provoke Conflict, Crises - POWER magazine

"conflict" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bZ36xX

https://ift.tt/3aYn0I8

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Egypt Warns Ethiopian Mega-Dam May Provoke Conflict, Crises - POWER magazine"

Post a Comment