In one respect, it’s a decades old story, as aged as the conflict of developers’ property rights and not-in-my-backyard homeowners.

In another, it’s a new story, one that is building to a crescendo as Greenville’s suburban growth balloons outward toward rural strongholds at its northern and southern end.

Containing that growth, reining it in for those rural landowners concerned that developers will slap six houses per acre on rural farmland, will always be in tension with homebuilders who seek to create housing and jobs for the explosive growth the county expects to see over the next 20 years.

But a seemingly simple solution has created a spark, an innocuous rule added deep within Greenville County’s land development regulations in 2018. Developers and homeowners have each sued the county, feeling jilted by planners' decisions. The county’s Planning Commission enforced the rule, then decided it couldn’t. Some homeowners tried to talk their neighbors into zoning to protect the rural character of their properties only to be met with threats.

Now there’s a proposal to change the rule to one that would better guide how many houses could be built on unzoned rural land. Some stakeholders, though, say the proposal would effectively lead to the zoning of all of the county’s unzoned land, 265,000 acres in all.

County officials say the land would still be unzoned, but the proposal would limit how many houses could be built in rural areas.

More than half of the county would be affected.

What happens next will shape the pace and location of growth in the Upstate for the next decade or more.

Adequate and compatible

Two sentences broken into three bullet points, inserted within the 190 pages of the county’s land development regulations when the rules were updated in 2018, aimed to add teeth to the rules that govern how and where subdivisions can be built.

Subdivisions would be approved if they met certain criteria. It must have adequate infrastructure – large enough roads in good enough shape to handle the traffic created by new homes. It must be compatible with the density of land uses around it. It must meet certain environmental standards regarding wetlands, flooding, endangered species and habitat, and historic sites or cemeteries.

It’s known as Article 3.1, and after its passage environmentalists and homeowners used it as a tool to urge county planners to reject subdivisions in unzoned areas of the county, locations where developers previously could put houses on lots as small as 6,000 square feet. If a developer with access to water and sewer wanted to put 140 houses on 20 acres next to a farm, they could.

Until Article 3.1 came along.

Article 3.1 of Greenville County Land Development Regulations

At the behest of homeowners, the Planning Commission immediately began to take Article 3.1 into consideration, particularly when deciding whether subdivisions were compatible with surrounding density.

The commission rejected four subdivisions in unzoned areas in two months during the summer of 2018, each time citing a lack of compatibility with neighboring land use density.

Developers complained that the county was destroying the future of housing developments in the county while homeowners who’d felt helpless against the onslaught of new projects breathed a sigh of relief and cheered the decisions.

The rule is too vague and allows the Planning Commission to make subjective decisions about unzoned land, the Homebuilders Association of Greenville wrote in a policy paper sent to The Post and Courier this week.

Then a developer sued the county, County Council and Planning Commission. He alleged a civil conspiracy against his development and challenged the constitutionality of Article 3.1. That case is still tied up in court. The National Homebuilders Association has backed the developer, paying legal fees.

The county has since reversed course; its legal staff told the Planning Commission it could no longer use Article 3.1 as a reason to reject rezoning requests for subdivisions.

The Planning Commission is inundated with Article 3.1 issues but cannot consider those factors when making its rezoning recommendations, said Steven Bichel, Planning Commission chair, to livestream viewers of its Aug. 26 meeting.

Michael Corley, an attorney with the nonprofit South Carolina Environmental Law Project, also believes the law needs to be revised. But until it is, he said it should still be enforced and that’s not happening.

County Council Chairman Butch Kirven said a judge has withheld a decision in the court challenge to give the county a chance to rework its law.

Kirven was hopeful that an amendment to Article 3.1 would solve some of the legal challenges and provide more clarity for developers, but as the council’s Planning and Development Committee plans to discuss that change Monday, it already faces stiff opposition.

Among those opposed? The powerful Homebuilders Association of Greenville and Greater Greenville Association of Realtors, which have each lobbied to deny the amendment.

Last Wednesday, the county Planning Commission voted 5-4 to recommend denial of the amendment.

A sliding scale

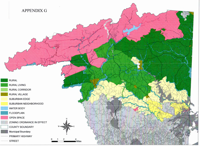

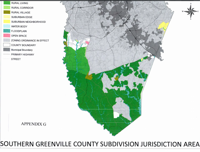

The amendment would set standards for how many houses could be built per acre on unzoned land. It wouldn’t affect land uses other than subdivisions, but would establish a Subdivision Jurisdiction Area for all unzoned land in the county, primarily in the northern and southern thirds of the county.

Within that area, the county would classify land on a sliding scale from rural to suburban neighborhood, just as it has done in its comprehensive plan updated in 2019. On rural land, houses would need at least two-acre lots. In suburban areas, houses could have one-third-acre lots.

Julie Turner has been fighting the density of a proposed development across from her 10-acre home and horse farm on Tigerville Road since 2018, Thursday, Aug. 20, 2020.

When Tigerville resident Julie Turner saw the amendment, she was thrilled.

Since the spring of 2018 she’s been fighting a proposed 31-home subdivision on 24 acres directly across two-lane Tigerville Road from her 10-acre horse farm.

When Niemitalo Inc., a pair of brothers who are developers from Inman, bought the acreage and put up subdivision signs, she said it was “game on.” She researched the county’s regulations, networked with neighbors and experts and leaned on her county councilman Joe Dill to find a way to keep the subdivision out.

She feared it would destroy the rural character of the winding road she lives on, with trees and pastures and a 600-acre farm nearby and a stretch of country dotted with single houses along the route through the hills north of Travelers Rest.

She’s built a file box since then of plans and documents and environmental white papers all geared toward defeating the subdivision and others proposed nearby. But outside the red brick ranch she and her husband share, she looked across the road, past the dark split-rail fence that surrounds her property and considered what may still happen.

“My property value as a horse farm would be impacted if a high density subdivision went in across the street because most people who want a horse farm don’t want to live near subdivisions if they’re trying to provide a quiet atmosphere for horses,” Turner said.

Despite her efforts, the Planning Commission initially approved Niemitalo’s plan. Then in a twist, it reconsidered its original vote, and citing Article 3.1, found that the plan didn’t fit the rural character nearby, Niemitalo’s plan was rejected.

Earlier this year, Niemitalo sued. He said the County Council conspired with the Planning Commission to reject his plan after it had already been shown to meet all of the requirements to develop. The lawsuit is pending, and if he’s successful, Brian Niemitalo said he still wants to develop his subdivision as he intended.

“You never win when you go to court but I just wanted to try to preserve a little bit of freedom in this country so when you buy a piece of property you can be reasonably certain of what you can do with it,” he said.

The county’s amendment, he said, would devalue land in the county by limiting the prospect for development.

Niemitalo isn’t alone in suing based on Article 3.1. A number of lawsuits have been filed, some from homeowners, some from developers in the three years since the county passed its new land development regulations. Michael Dey, vice president of government affairs with the HBA of Greenville, said a lawsuit is the only recourse to a Planning Commission decision for both homeowners and developers.

Since the rule is vague and subjective, it’s led to confusion and lawsuits, he said.

County attorney Mark Tollison declined to comment on the lawsuits because they are pending.

Opposition and options

When the proposed amendment came before the Planning Commission on Wednesday, several commissioners tried to stall a vote, saying the week they’d had to read through the changes wasn’t long enough. When that didn’t work, several began to speak out in opposition to the proposal.

One of the most vocal was commissioner and developer Frank Hammond, who said the plan would essentially zone 51 percent of the county that is now unzoned.

That’s the position the HBA took as well, saying in its official opposition that the county proposed to set density controls in unzoned areas because “they would like to zone the unzoned areas.”

That’s not true, Tollison said. The county isn’t setting zoning at all, but is setting minimum lot sizes for residential development, which it has the authority to do by state law, he said.

The realtors association added its opposition this week because in its eyes the county would devalue the price of rural land by limiting its development potential, said Chris Bailey, government affairs director with GGAR.

Much of the rural land in question already faces development limitations in reality because of lack of access to public water or sewer. New subdivisions built with septic systems will by necessity have larger lot sizes, Dey said.

Northern Greenville County Subdivision Jurisdiction Area as proposed by changes to the Greenville County Land Development Regulations.

Even so, the proposal is sure to rankle independent-minded landowners in the county’s Dark Corner and southern piedmont.

When the state enabled Greenville County to set zoning in 1994, Greenville and other Upstate counties left many places unzoned because residents were staunchly opposed.

In recent years, efforts have been made to add zoning in some of those unzoned areas to vastly different reception from neighbors.

Southern Greenville County Subdivision Jurisdication Area as proposed in an amendment to Greenville County's Land Development Regulations.

In southern Greenville, after a developer proposed turning an 82-acre site on narrow, poorly-maintained county roads into a subdivision, neighbors banded together in a two-year process of gathering support to petition the county for rural zoning.

They succeeded in zoning more than 7,000 acres to allow either one house per acre or one house per three acres, depending on location, said Jim Moore, who helped found a nonprofit Citizens for Quality Rural Living.

Turner, the Tigerville homeowner, tried to launch a similar effort with her neighbors. She organized a meeting at a nearby church and invited county planning staff to discuss different types of zoning. The meeting was canceled after the church told Turner it had received threatening calls from those opposed to zoning.

A sign Turner placed to advertise the meeting was defaced.

“How do those people come together and we’re fighting a war up here?” Turner said. “Northern Greenville is not southern Greenville. I don’t know if it’s the Dark Corner influence or something deeper than that in people’s DNA.”

Clear rules needed

All stakeholders agree that Article 3.1 isn’t working. The HBA wants it tossed entirely or amended with their input. Corley, the environmental attorney, said the amendment as proposed would satisfy landowners concerned about preserving the rural character of the unzoned areas, which also have the most environmental value. Turner said she’d be fine with a subdivision across the street that had 2-acre lots for houses.

Mostly, homebuilders just want the surety of knowing the rules before they buy land or propose a project, Dey said.

If Greenville County continues to grow as it is at twice the pace of the national average, it will add nearly 200,000 new residents in the next 20 years, Dey said. Those new residents need homes, and increasingly developers are looking to neighboring counties with cheaper land and less regulation, he said.

Niemitalo said he doesn’t plan to buy land to develop in Greenville County again.

“They’ve achieved their goal on that regard,” he said. “They want to throw so much red tape in front of anybody who develops. I guess they’ve won.”

"conflict" - Google News

August 30, 2020 at 09:03PM

https://ift.tt/34Lsd6J

Conflict, confusion over zoning rule: As suburbs swell, a rural rift in Greenville County - Charleston Post Courier

"conflict" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bZ36xX

https://ift.tt/3aYn0I8

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Conflict, confusion over zoning rule: As suburbs swell, a rural rift in Greenville County - Charleston Post Courier"

Post a Comment