Sarah Schulman is a playwright, an author, and a queer activist. She is also a professor of creative writing, and once, a number of years ago, she learned that a male graduate student maintained a blog where he wrote about his crush on her. He wrote that he was in love with her; he wrote that he wanted to fuck her; he wrote about her appearance in a way that made her feel bad. She told her colleagues what was happening, and their response was unanimous: He was “stalking” her. They advised Schulman to report him to a supervisor.

She considered this. She was uncomfortable with what was happening, and she wanted it to stop. But she was also uncomfortable with her colleagues’ advice. “I realized that the more I saw myself as being victimized by this person, the more support I had from my colleagues,” Schulman told me. “They would wrap me in the comfort of their protection. And I found this very disturbing. Because no one said to me, ‘Why don’t you ask him what he thinks is going on?’ ”

In her mind, stalking meant something like “when your ex-husband is in front of your house with a gun.” She wasn’t frightened of her student; she was disconcerted. “Stalking is a real thing, and people lose their lives to stalking,” Schulman said. What she had on her hands was not that: It was a situation in which “somebody is feeling something and another person feels uncomfortable about it. That is often called stalking, but it’s not stalking.” She decided to call her student and talk to him about it.

She learned, first of all, what a blog was and what sorts of things people wrote there — this was the early aughts, and she hadn’t really known. So there was a generational divide at work. She also learned she was the first teacher who had taken his writing seriously; he’d probably gotten “over-involved” because of that. They had a few conversations, he said what he wanted to say, she transferred him to another adviser, and no further issues arose. Looking back, “the scary thing was how much reward was waiting for me if I presented myself as victimized,” she said — that promise of community embrace.

Schulman describes this episode in a book she wrote some years later, Conflict Is Not Abuse. The book’s central insight is that people experiencing the inevitable discomfort of human misunderstanding often overstate the harm that has been done to them — they describe themselves as victims rather than as participants in a shared situation. And overstating harm itself can cause harm, whether it leads to social shunning or physical violence.

Schulman argues that people rush to see themselves as victims for a variety of reasons: because they’re accustomed to being unopposed, because they’re accustomed to being oppressed, because it’s a quick escape from discomfort — from criticism, disagreement, confusion, and conflict. But when we avoid those uncomfortable feelings, we avoid the possibility of change. Instead, Schulman wants friends to hold each other accountable, ask questions, and intervene to help each other talk through disagreements — not treat “loyalty” as an excuse to bear grudges.

A wide-ranging exploration of human relationships and responsibility, Conflict Is Not Abuse was the rare book published in October 2016 to be more relevant instead of less by November’s end. It was a book for which Schulman could find no U.S. publisher; which was released by Arsenal Pulp, a queer Canadian press that paid her a $2,500 advance; and which — like Debt, by David Graeber, or All About Love, by bell hooks — was the kind of accessible work that wins a radical figure unexpected fans. The book offers readers a clarifying lens through which to consider the fraught encounters of our era of discontent: between police and protesters; between writers and their readers; between colleagues, neighbors, and friends. It is now in its seventh printing.

Clear, provocative and concise, “conflict is not abuse” is a perfectly aerodynamic unit of intellectual achievement. It has flown farther, faster, than Schulman ever thought it would. In part, this is because the mantle of victimhood she argues against has become more widely recognized and discussed even as it has remained exceedingly commonplace. Claudia Rankine, a friend of Schulman’s for nearly 30 years, said the Central Park encounter between Amy Cooper and Christian Cooper was emblematic of the pattern Schulman describes. Christian Cooper was birding in May when he asked Amy Cooper to follow park rules and leash her dog; she responded by calling the police and claiming she was in danger. “It’s a threat that is imagined but then weaponized in a society that is systemically racist,” Rankine said.

Schulman’s analysis scrambles familiar ideological lines. She looks askance at trigger warnings; she also looks askance at Zionism. She considers the way accusations of sexual threat have been used against Black and queer people and then uses that understanding to extend empathy to those accused of sexual harassment. She tries to dissect the internal logic of police brutality and domestic abuse. Her ideas’ appeal lies in offering a new way to consider seemingly intractable problems and in drawing lines between our political ideals and the way we behave in daily life. (“There are a lot of progressive people who are very petty,” Schulman told me. “So what kind of progressive world can they build?”) They’re complicated ideas, and the book takes them in directions sure to give every reader something to disagree with. But — at least within the realm of personal relationships — they also come down to an almost kindergartenishly simple dictum: Talk, listen, work things out.

As she makes clear, this directive is simple but hardly easy. One of the reasons so many people claim victimhood is that, in Schulman’s observation, having your pain taken seriously is a gift only victims seem to receive. “It’s about being eligible for compassion,” she told me. “But everybody deserves support, regardless of what position they’re in.”

Schulman began writing Conflict Is Not Abuse in 2014, during a summer shadowed by the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, by the death of Eric Garner on Staten Island, and by the deaths of some 2,000 Palestinians in Gaza. These events seemed to her to share a form. Soon, she was talking with her students about Garner; she was having long arguments on Facebook about Israel; she was angry about what she saw as terrible injustices, but she was also interested in how they came to be. How did a violent cop or a member of the Israeli army rationalize what he or she had done? Listening to the explanations on offer suggested that anxiety and fear had given rise to a “mortal overreaction by an oppressive force,” Schulman told me. The cops and Israeli soldiers had seen themselves as victims and lashed out.

The results, in those cases, were fatal. But Schulman began to recognize the same pattern playing out in her private life: a misplaced sense of danger, an overreaction, then a rift that came to seem impossible to repair. Two friends would have a fight, then one would persuade the rest of their clique to turn on the other. Someone would express a dissenting opinion, then face accusations of violence and calls for punishment. Schulman saw people turning away from the challenges of conflict and instead asking some larger body — a group of friends, a college bureaucracy, the state — to ratify their status as victims and intervene on their behalf.

“A nonfiction book is the story of an idea,” Schulman told me — and the analysis found in Conflict Is Not Abuse, she writes, brings “fifty-seven years of living and thirty-five years of writing to a critical conclusion.” In this case, the idea’s story is perhaps also her own.

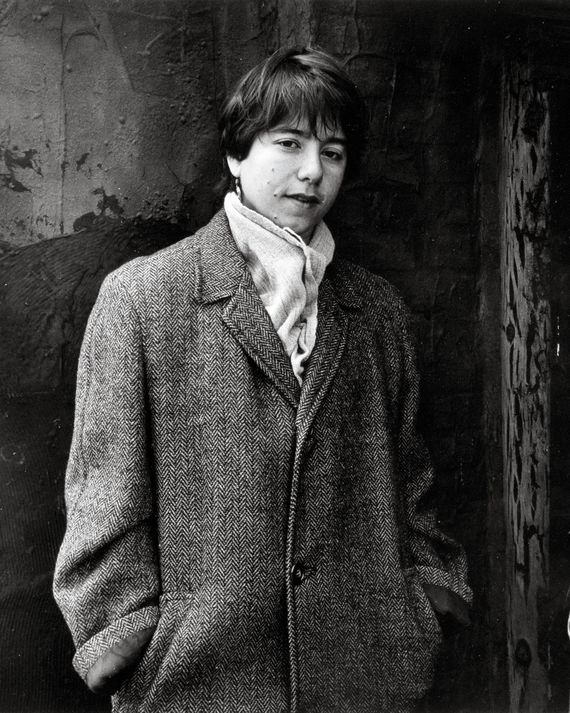

Schulman’s family lived on 10th Street when she was born, in 1958; she lives on 9th Street now, and when we first met, in very early March, it was at a boutique hotel on 8th. She has a soft face, a deliberate cadence, and wry wit. Of her status as a fixture in the neighborhood, “the only thing older than me is Veselka,” she said. (The restaurant opened in 1954.)

Schulman has stayed close to where she was born but not because it was ever an easy place to be. Growing up Jewish and middle-class in Manhattan, she came from what she has called a Holocaust family, with a history “typical of my Jewish generation: soaked in blood, trauma, and dislocation.” It was also a family in which, she has said, “being a smart female was an insurmountable problem and being gay was the ultimate disaster.”

In Conflict Is Not Abuse, she describes going to her high-school guidance counselor for help: “I was sixteen in 1975 and faced the brutality of my parents’ homophobia,” she writes. In response, the counselor “told me not to tell my classmates that I was a lesbian because they could shun me.” After graduation, she left the city for the University of Chicago, but she soon returned to attend Hunter College, where she studied with Audre Lorde. By 1979, she was working as a reporter for the city’s underground queer press and waitressing at a coffee shop in Tribeca.

While waiting tables, she managed to write and publish two books, but some of the neighborhood artists who were her regulars suggested it might be useful to get an M.F.A. She enrolled in a City College writing program taught by Grace Paley, and on the first day, she read aloud an excerpt from her current project — her third novel, which had a lesbian narrator. The other students assumed the narrator was a man. Paley asked Schulman to come to her office after class. “Look, you’re really a writer,” Schulman remembered Paley telling her. “You don’t need this class. Go home.” She dropped out. That third novel, After Delores, was a noirish detective story narrated by a lesbian waitress, and it garnered Schulman’s first book review in the New York Times. (“I read the book, found the lady sleuth to be a vomit-stained, coffee-stained, bloodstained lesbian with great self-doubt and a rather severe hygiene problem, and decided I liked it,” wrote the cowboy singer and writer Kinky Friedman in his enthusiastic review.)

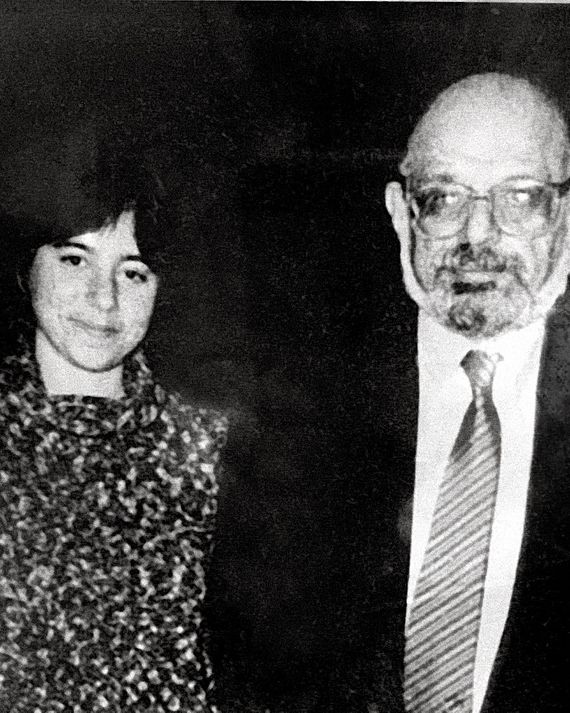

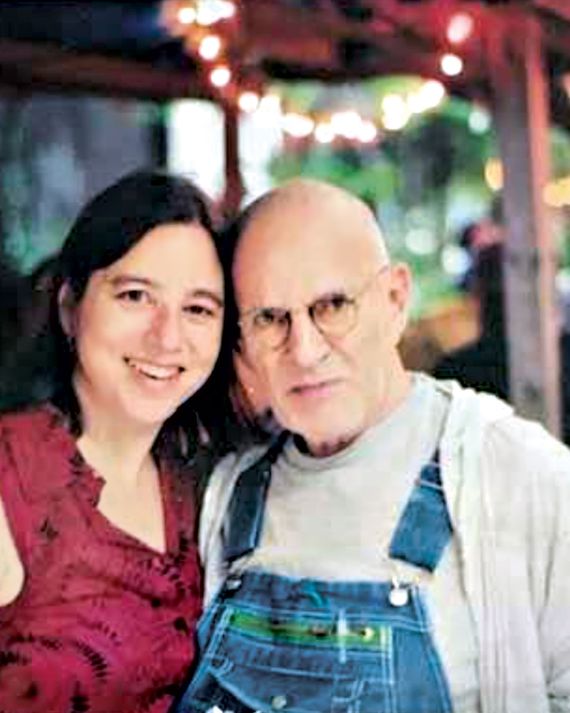

In the ’80s, Schulman was finding success and also finding a community: a downtown world of queer artists and leftists throwing parties and forming ad hoc political groups and collaborating on projects — like the New York Lesbian & Gay Experimental Film Festival, which Schulman started in 1987 with filmmaker Jim Hubbard. “We were sitting in her apartment smoking a joint,” Hubbard recalled. “Sarah handed me the joint and said, ‘We should do a lesbian and gay experimental-film festival.’ And I said, ‘I’ve always wanted to. When should we do it?’ And Sarah thought for a little bit and said, ‘September.’ ” The festival (now called MIX NYC) went on to host the first New York screening of Paris Is Burning and early work by Todd Haynes.

Even as that community was flourishing creatively, it faced the devastation of a plague. Schulman and her peers watched friends and lovers die terrible deaths from AIDS as powerful institutions mostly shrugged. The scale of mainstream indifference to the plight of AIDS victims makes comparison with, say, the current coronavirus pandemic difficult. This was not a disease that most Americans saw as a crisis that had anything to do with them. “Why Make AIDS Worse Than It Is?” read the headline of one New York Times editorial. “The disease is still very largely confined to specific risk groups. Once all susceptible members are infected, the numbers of new victims will decline.”

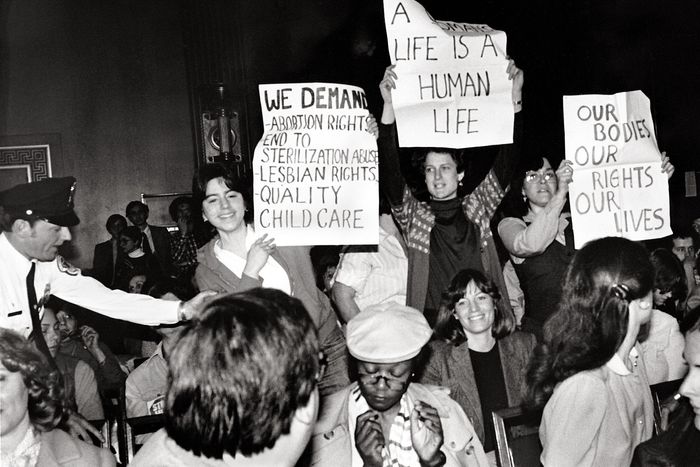

That indifference galvanized a generation of activists. The same year Schulman and Hubbard founded their film festival, Larry Kramer spurred the founding of ACT UP. Schulman and Hubbard both joined. ACT UP members infiltrated the New York Stock Exchange, where they chained themselves to a balcony and disrupted the opening bell; they shut down FDA headquarters; they covered Jesse Helms’s house in a giant condom. The group’s combative spirit remains bracing. When Kramer died in May, the Times still seemed disturbed by the force of his rage. “He worked hard to shock the country into dealing with AIDS as a public health emergency,” read the subheading of his obituary. “But his often abusive approach could overshadow his achievements.” In this context, however, being “confrontational” (a word the Times later swapped in for “abusive”) was not a quirk of personality; it was the point. And between the federal government (or the New York Times) and Larry Kramer, which party was really in a position to “abuse” the other? Indeed, remarked one observer on Twitter, “calling Larry Kramer ‘abusive’ is actually an ancient mystic ritual to summon Sarah Schulman.”

Schulman is devoted to preserving the memory of the ACT UP era and of the hard work that its accomplishments required. In June 2001, she and Hubbard began the ACT UP Oral History Project, for which they recorded interviews with more than 180 surviving members of the group. Hubbard and filmmaker James Wentzy filmed, and she asked questions. “She would be in this intense relationship with the other person — a little bit like therapy,” Hubbard said.

The oral histories have also become the basis for Schulman’s next book, which Farrar, Straus and Giroux will publish in 2021. Her approach to the material is at once unsentimental and resolutely personal. As she writes in her Oral History statement, the project calls on the same sense of responsibility with which she’d been raised to regard the Holocaust: for remembering the dead, identifying the perpetrators, and “refusing revisionism” in a story of mass death. Her new book will push against the view of ACT UP as an organization of primarily affluent white gay men.

Over the years, Schulman has been wary of the way queer stories tend to enter the mainstream — homogenized and flattering to straight audiences — and has argued forcefully against the diminishment she sees. “People are talking about some remarkable similarities between the hit musical [Rent] and Sarah Schulman’s novel People in Trouble,” read a 1997 item in this magazine. That 1990 book concerned an AIDS-era love triangle among queer New York artists and activists; the non-Puccini portions of the 1996 musical bear a clear resemblance to the novel, both in the outlines of relationships and in specific plot points. The crucial difference, of course, is that in the book, the queer characters are the center of the story, where in Jonathan Larson’s musical, they’re pushed to the side. “Schulman is angrier about the depiction in Rent of gay people and the AIDS crisis than any allegedly lifted material,” wrote the reporter. The musical sent the message that “straight people are the heroic center of the AIDS crisis,” Schulman told him. (The episode became the kernel of her 1998 book, Stagestruck, on the recent commodification of queer culture.)

The Lesbian Avengers, a group Schulman co-founded in 1992, carried the oppositional spirit of ACT UP in new directions. The journalist and City College professor Linda Villarosa recalled finding herself in Schulman’s social circle in those years: “I remember her being so smart, so intense — you know, somebody who just really stuck to their guns and made things happen.” Things like the Dyke March: an annual permit-free protest march ahead of official Pride events, orchestrated by the Lesbian Avengers and staged in New York for the first time in 1993. “I was like, ‘What? A human being can just do that?’ ” Villarosa said. “You could decide that lesbians were going to take over part of the street? Be topless?”

As queer people were increasingly invited to identify with mainstream power in the ’90s and aughts—as gay rights gained purchase, as Pride went corporate — new questions arose. The movement from outsider to insider, to identifying with power, presents a crucial turn in Conflict Is Not Abuse. How might people who were once oppressed then become oppressors? For Schulman, this reckoning arrived in 2009, when she was invited to give a talk at Tel Aviv University about Ties That Bind, her book on familial homophobia. A friend told her she couldn’t go — there was a boycott.

What boycott? Schulman wondered. “So I started to find out about it, and I realized that I couldn’t go.”

She declined the invitation and began to examine how she’d come to this pass. “I had to face all the prejudices I’d been raised with,” she told me. Having grown up with the specter of the Holocaust, she confronted the possibility that Jews, having been victims, might now be perpetrators as well — and that, in fact, the ways that they’d been victims in the past might blind them to their own power to abuse. “I came to this very, very late, and I feel very badly about that,” she said. “At some point, if you want to have a real life, you have to say, ‘I did that then, this is why I did it, but I don’t have to do it.’ It’s possible to do that. You don’t have to be a martyr or a saint to do that.”

The subtitle of Conflict Is Not Abuse is “Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair.” The last of those three phrases is one Schulman also uses in The Cosmopolitans — the novel she published the same year as Conflict Is Not Abuse. Set in the 1950s, it centers on two friends in New York City who have lived next door to each other for 30 years. “I know there is cruelty in life,” The Cosmopolitans’ heroine says. “But I believe that it can be followed by reconciliation.” She says she believes “in the duty of repair.” Life in a family, in a community, in a place like New York City, seems to demand a belief that repair and resolution are possible, and that their pursuit is necessary, if we’re all going to keep living together.

Perhaps Schulman’s most provocative move in Conflict Is Not Abuse is her insistence that overstatement of harm happens everywhere: People in power who face criticism can overstate harm, but people who have previously suffered — who have lived through real harm — can do it too. For those in positions of dominance, she told me, “opposition feels like an attack.” Meanwhile, for those who have survived trauma, “it’s sometimes so hard to just keep it together that being asked to be self-critical can feel like your whole world is going to fall apart.” The explanation is different, but the result can be similar.

For readers focused on establishing the gravity and reality of domestic abuse, Schulman’s critical scrutiny of the term’s use may seem counterproductive. Her broader point, though, is that we live in “a culture of underreaction to abuse and overreaction to conflict,” as she writes. “Abuse” happens in situations where one person has direct power over the other; her analysis of “conflict” concerns situations of mutual participation, or in which the powerful person is in denial.

These distinctions may be clearer in Schulman’s telling than in real life, where the question of who has power (a pop star? A music critic? The pop star’s army of online fans?) can prove more elusive than one would hope. At the same time, Schulman’s refusal to flatten human experience into politically useful platitudes—she doubts, for example, that “no” always means “no” — will alarm some readers no matter what.

Even before the book was published, it was subject to a backlash on Tumblr. “People were furious about this book,” the writer and podcaster merritt k told me. “Just the title sparked so much outrage. People saw Conflict Is Not Abuse and basically thought, Oh, this is someone telling me that I wasn’t abused.” A friend and fan of Schulman’s, she took to Goodreads, writing a positive if measured review. “Many of the examples Schulman describes resonated with me, also a queer woman, but they may ring hollow to those outside these communities,” she allowed.

Schulman believes that those who read her book as denying their own experiences of abuse are misunderstanding her, but she also seems interested in the defensiveness the book provokes. She heard from one reader who was upset that Conflict Is Not Abuse “made her question whether the partner she had accused of being abusive really was abusive,” she told me. “She saw that as an assault, that it made her doubt herself.”

Rankine told me that she and Schulman talked a lot about the title of the book and the question of whether conflict itself might at a certain point become abusive. “I felt our position on that is different,” she said. “I do feel like there’s a moment when you can’t really put yourself in that position again — to be in a position of conflict willingly, because the trauma and abuse is too much.” She acknowledged a kind of utopian strain in her friend’s thinking. “Sarah is committed to action — things becoming newly formed,” she said. “In that way, I think she’s a greater optimist than I am.”

Surely, progress for broken people and broken countries demands some belief in the possibility of repair. Schulman’s analysis of our political straits doesn’t come with a to-do list of actions for directly tackling the structural problems she recognizes. She warns that we enhance state power when we call the police, but she doesn’t prescribe how to attack it at the root. Seeing why a violent cop might behave the way he does is one thing; getting that cop to understand his own behavior with enlightened self-awareness is a greater challenge.

A more serious criticism, then, might have to do with practical application of Conflict Is Not Abuse. Reading Schulman’s book is invigorating: It offers the experience of reconsidering the world around you and bumping up against habits of mind you didn’t realize you had. It’s hard to imagine finishing it without feeling some pang of uncomfortable recognition or without reliving that pang the next time you are tempted to take one of the shortcuts she abhors — joining in when friends bemoan a loathed ex, ignoring a text instead of picking up the phone to make things right.

But people take shortcuts for a reason. Even before you arrive at the obstacles to solving problems like state violence, where implementing her theories is hard to imagine, just upholding Schulman’s ideals within the personal sphere is a daunting task. “The social world she’s describing is so time consuming,” her friend Lana Dee Povitz told me. It demands constant self-scrutiny, ongoing dialogue, diligent fact-finding, and availability for intervention in the personal lives of one’s friends. “That world she’s asking for is nearly impossible under capitalism,” Povitz said.

Povitz was a 26-year-old living in a queer collective in Brooklyn when she met Schulman. It was 2012. Povitz was part of a group of 20-somethings just learning how to organize — they wanted to fight gentrification — and she ran a book club that was reading Schulman’s 2012 book, Gentrification of the Mind. After Povitz got in touch about reproducing some material, Schulman volunteered to come speak to her group.

Schulman wanted to start by hearing about them; she was curious about their lives and their work. She asked questions. She listened. And she asked more. Did they know their neighbors? Povitz remembered Schulman asking. Did they help with the neighbors’ kids? Did they know the local churches? Did they know what work the churches were already doing?

“We were just like, ‘No, no, no, no, we don’t,’ ” Povitz told me. “ ‘Oh my God, we don’t.’ ”

Schulman “doesn’t do a lot of the feminine niceties that a lot of women seem trained to perform,” Povitz said — things like the agreeable smiling and mirroring that smooth over mild social disjuncture and keep conversations rolling comfortably along. Instead of, say, offering gentle encouragement, Schulman made it plain how deeply “unimpressive” she found the group’s efforts. They were not doing the things Schulman believed necessary to make a material difference in others’ lives, so she said so. “It was kind of devastating,” Povitz recalled.

Today, Povitz teaches at Middlebury; she’s a historian of U.S. social movements, and she often assigns Schulman’s work. When we spoke, she was still audibly pained by the memory of their first encounter. Povitz remembered that plenty of people were upset: They were self-conscious, they got defensive, they found Schulman to be “mean and blunt.” But Povitz also saw something else. “There were people who were really put off,” she said. “And then there were people who were like, This is hard, and I want to sit with it.” The people in the group who were willing to sit with criticism, who could hear unflattering opinions and have difficult conversations — “those were the people I knew I wanted to identify with politically,” she said. That willingness was valuable, Povitz realized, even if it was rare.

Upon meeting her new editor at FSG, Jackson Howard, Schulman told me, she made an immediate request. “The first day I was like, ‘Treat me like a 60-year-old man,’ ” she said. “And he did!” Since then, their relationship has been “great.”

Howard laughed when I asked if he remembered the exchange. He said he was “probably trembling” at the time. Howard is 26, and he’d admired Schulman’s work since reading After Delores in a college class called Bad Homosexuals — but it was more than that. “Sarah has a reputation for being a hard-ass,” he recalled of his impression before that first breakfast meeting. “Even in her writing, she is uncompromising. She is cutthroat. She does not back down from her positions.” He sought to win her trust, knowing that he represented the kind of institution that traditionally had not been on her side. “I mean, she is somebody who’s made a career out of conflict and out of confrontation and out of provocation — but never for the sake of doing it.”

In this sense, Conflict Is Not Abuse is “a really good window into her,” Villarosa told me. “I think she wants to tell you, ‘It’s okay for us to have conflicts.’ ” Perhaps the need for reassurance is somewhat generational. “In the ’90s, that was big — in ACT UP, people were just coming to blows, practically, and I think now people are more afraid of conflict than we were back then.”

Schulman’s comfort with conflict is well known. (In 2005, she was the subject of a write-up in the Times with the headline “Who’s Afraid of Sarah Schulman?” that now reads as arguably sexist and startlingly snide.) “I think what people don’t as much understand about her is that she’s very kind,” Villarosa said. She is a frequent dinner guest at Schulman’s home, where meals are planned generously and guests’ assistance is refused. “You schlep up however many floors to get to her place in that tiny apartment,” Villarosa told me. “Her bedroom is an inch away from the living room, you know, but it’s like a salon, going to her house, because there will always be a couple of other smart people over there.”

The last time Villarosa was over, it was Lydia Polgreen and Rankine. (Rankine and Schulman also talk on the phone every Sunday.) Schulman once hosted Villarosa’s mother after she and Linda debated whether queer people are inevitably let down by their families; Villarosa had insisted (contra Schulman’s convictions about familial homophobia) that her mother was one of her best friends. Sometime later, Schulman asked Villarosa whether she could invite “Mrs. V” to dinner. Mrs. V and Schulman had a lovely time and talked at length about the theater. “She just loves to get people in a room to talk about ideas and to sit and help her expand her mind,” said Villarosa. “And also to give her opinions, and I really, really appreciate that about her.”

“My experience is that she’s interested in the thing that is interesting to you,” said Matt Brim, a friend who, like Schulman, teaches at CUNY’s College of Staten Island. “She wants to know how you’re thinking about it. She wants to encourage you to think as well as you can about the thing you’re thinking about.” A few years ago, Schulman invited Villarosa to give a lecture about the reporting she’d done on HIV/AIDS over the years. “She has such high standards, so I wanted to do a really good job,” Villarosa said. She went back to her earliest work for Essence in the ’80s and carried through to the present, describing the ongoing danger of HIV/AIDS for gay and bisexual Black men in the South. Schulman found the material arresting. After the lecture, “she sat me down and she said, ‘This is really important. You need to do something else with this.’ ” Villarosa had assumed what she was saying was familiar; Schulman was adamant that it was news. “And that became my first cover story for The New York Times Magazine,” Villarosa said.

merritt k told me she saw Conflict Is Not Abuse as most valuable within small communities — queer communities, radical communities, whose members can’t afford to turn on one another. For them, it conveyed a message that “hey, guys, if we’re running around trying to take each other out constantly, that’s not a good place to be.” Before the lockdown, merritt would go over to Schulman’s apartment every few months. There, Schulman would pour her a glass of whiskey and they’d talk about what they each were working on. “I don’t know if she would like this,” merritt said, “but I kind of think of her as my queer mom.”

For Schulman, the classroom is a microcosm where it’s possible to apply the book’s principles on a manageable scale. “In a healthy educational forum,” she writes in Conflict Is Not Abuse, “students engage materials regardless of agreement or comfort level and then analyze, debate, critique, and learn from them, addressing the discomfort as well as the text.” For this reason, in the classroom, she has a “no censorship” rule. “Students can engage any subject, event, or character and use any language that they feel is appropriate,” she writes. “Any student who has criticism, insight, or objection to these elements has the equal right to express their views in detail. This has been my policy for sixteen years without a single complaint.”

Schulman often teaches a Friday-night fiction class from 6:30 to ten. “So my students have worked all week, they’ve taken care of their kids, and they’re coming to write fiction on Friday night,” she said. With the pandemic, her students’ challenges are more apparent than ever. “Their children are home from school, their parents are unemployed, they don’t have good Wi-Fi, and also they don’t always want their families to hear what their class discussions are like,” she told me.

She has found that teaching at a working-class institution like hers can clarify the debates of campus culture. “No one has ever asked for a trigger warning,” she said. “It’s a very entitled position to believe that you have the right and the ability to control other people.” When she visits other schools, the contrast is stark. She told me she remembered an exchange that followed a talk she once gave at Columbia. “There was a girl there who was Black, and she was from Queens, and she was saying, ‘In my neighborhood, I was taught to be resilient. And then I come to Columbia, and they say you should be protected. Which is better? Resilient or protected?’ ” For Schulman, the answer was obvious.

“I was like, ‘Resilient!’ ”

As she was writing the book, she did not expect trigger warnings or “cancel culture” to become focal points of discussion.

“I didn’t even really know about cancel culture,” Schulman told me. “I didn’t know the phrase.” But her talks and readings from the book drew the largest audiences of her career; the crowds were young, “and that’s what they wanted to talk about.” Now she sees a document like the recent “Letter on Justice and Open Debate” published in Harper’s as a “classic example,” she said, of the dynamic she described in her book: People from a “dominant culture feel threatened” and are reacting as if danger is afoot.

“The idea of free speech is being co-opted by the right,” she told me. “The answer is more speech, not less.” The risk of trying to limit speech, in her view, is that limitations will always be turned against the most vulnerable first. She pointed to the tendency to link speech in defense of Palestinians with anti-Semitism — a rhetorical move favored by, for example, Cary Nelson and Bari Weiss, who numbered among the signatories of the Harper’s letter. (Last year, Weiss was photographed at home, a copy of Conflict Is Not Abuse visible on her shelf. She told me she had not read the book and that it was a gift.)

When Schulman and I first spoke in early March, she was optimistic about “the big-tent movement” the Bernie Sanders campaign looked poised to assemble. “Well, you know,” she said when we spoke this summer, “there is a big-tent coalition in the street.” In the months since, the world had by most accounts fallen apart, fragmenting in ways that appeared shocking even as the pattern of the fault lines was familiar. Victimhood and threat were terms once again up for grabs — as federal agents turned tear gas on peaceful protesters, as entrenched elites ran for cover. Collective failures of communication and understanding — on matters as seemingly innocuous as germ theory — became more apparent and more dire.

Nearly four years after publishing a book that argued strenuously against calling the police, Schulman was pleased to see more people coming around to the idea. And the spasms of self-scrutiny shaking institutions across the country struck her as a somewhat predictable turn of events. “They wanted to bring in people of color and keep the organization the same—and that’s an unreasonable demand,” she said. “If the demand is that every cultural institution should be controlled by people of color, I’m fine with that.”

A lifetime of activism has left her with a complex appreciation for the practical matter of demands. “I’m very concretely focused,” she said. “I like when movements have reasonable, winnable, and doable demands and build campaigns toward them. But those kinds of movements are the most successful when they’re also simultaneously utopian movements.” The spirit that animates Schulman’s work, a sense of risk and possibility in difference, seems all the more urgent now — and all the more difficult to conjure. “The fact that something could go wrong does not mean we are in danger,” as she writes in the first chapter of Conflict Is Not Abuse. “It means that we are alive.”

*This article appears in the August 3, 2020 issue of New York Magazine.

"conflict" - Google News

August 03, 2020 at 08:31AM

https://ift.tt/2XCfHCn

Good Conflict - The Cut

"conflict" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bZ36xX

https://ift.tt/3aYn0I8

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Good Conflict - The Cut"

Post a Comment